Some WNY foundations are using old money for new ideas

The Buffalo News

When Greenard Poles asked one of his clients at a free tax clinic why her address changed, her answer delighted him: She bought a house with some of the $7,500 tax refund he helped her get by filing two years worth of returns, including an extra $2,000 a paid preparer missed in one year.

"Now she's a taxpayer. A property taxpayer," said Poles, director of a free tax preparation center.

The tax office, where Poles works with volunteers who quietly fill out tax forms from a warren of cubicles, is inside the Tri-Main Building, the converted windshield wiper factory where John R. Oishei made some of the fortune that led to his namesake foundation.

As it turns out, it was the John R. OisheiFoundation that gave $450,000 to the United Way to revamp Erie County's collection of free tax centers -- set up new ones and publicize existing ones -- to help the working poor retrieve tax refunds the IRS said Buffalo residents weren't claiming.

With the foundation's cash infusion, the tax centers helped clients retrieve almost $41 million in three years.

This is part of the new style of philanthropy-fueled poverty assistance.

A Buffalo News study of foundation giving in 2006 found that foundations gave more money to medical research, education and culture than to human services -- a category that represents some of the most direct giving to poverty-related programs.

Yet as Buffalo becomes poorer -- its ranking as one of the nation's poorest for the last two years drew particular attention -- some foundations say they want to find ways to provoke lasting change in the midst the city's overwhelming poverty.

That's the goal of the tax program, which now begins its fourth year, with the Tri-Main office newly expanded to include financial planning services.

Perhaps, Poles said, more people could be encouraged to use tax refund money to buy houses. Turning rent checks into mortgage payments might lead to ambition: to strengthen communities and fix neglected neighborhoods.

Maybe, he said, his client's drive will catch on.

"Hopefully, the property next to her can either sell or be developed," he said. "And now we have a community. Now we have a street. Now we have a neighborhood that is benefiting from all of their efforts, but in one part benefiting from their tax return."

The amount of money foundations pour into such individual programs is far less than the single-year totals that went to the arts: In 2006, $2.7 million went to the BPO for its endowment campaign, and that year $2.3 million funded the local collection of Frank Lloyd Wright building projects.

Even so, some foundations want to encourage innovation, such as the "social" venture capital fund Oishei has been thinking of creating with others to loan money to for-profit operations that do social good, such as the Urban Roots garden center that opened in an ailing West Side neighborhood and the Lexington Co-op on Elmwood Avenue. Or programs such as the tax centers.

Some foundations say the task involves sometimes abandoning passive check writing, overseeing donations like they are investments, encouraging collaborations and creating programs. Boards and trustees have even altered mission statements to better focus on poverty and economic development.

"A foundation's power far exceeds anything they could do with their grants," said Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker, president and CEO of Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo. "Foundations have stuck to their knitting, so to speak, in giving grants. That's insufficient for the type of change our communities deserve. There's a lot of leadership in foundations that's not being realized."

While foundations still give money in traditional ways -- funding scholarships, food pantries, after-school care and refugee outreach, for example -- they have also:

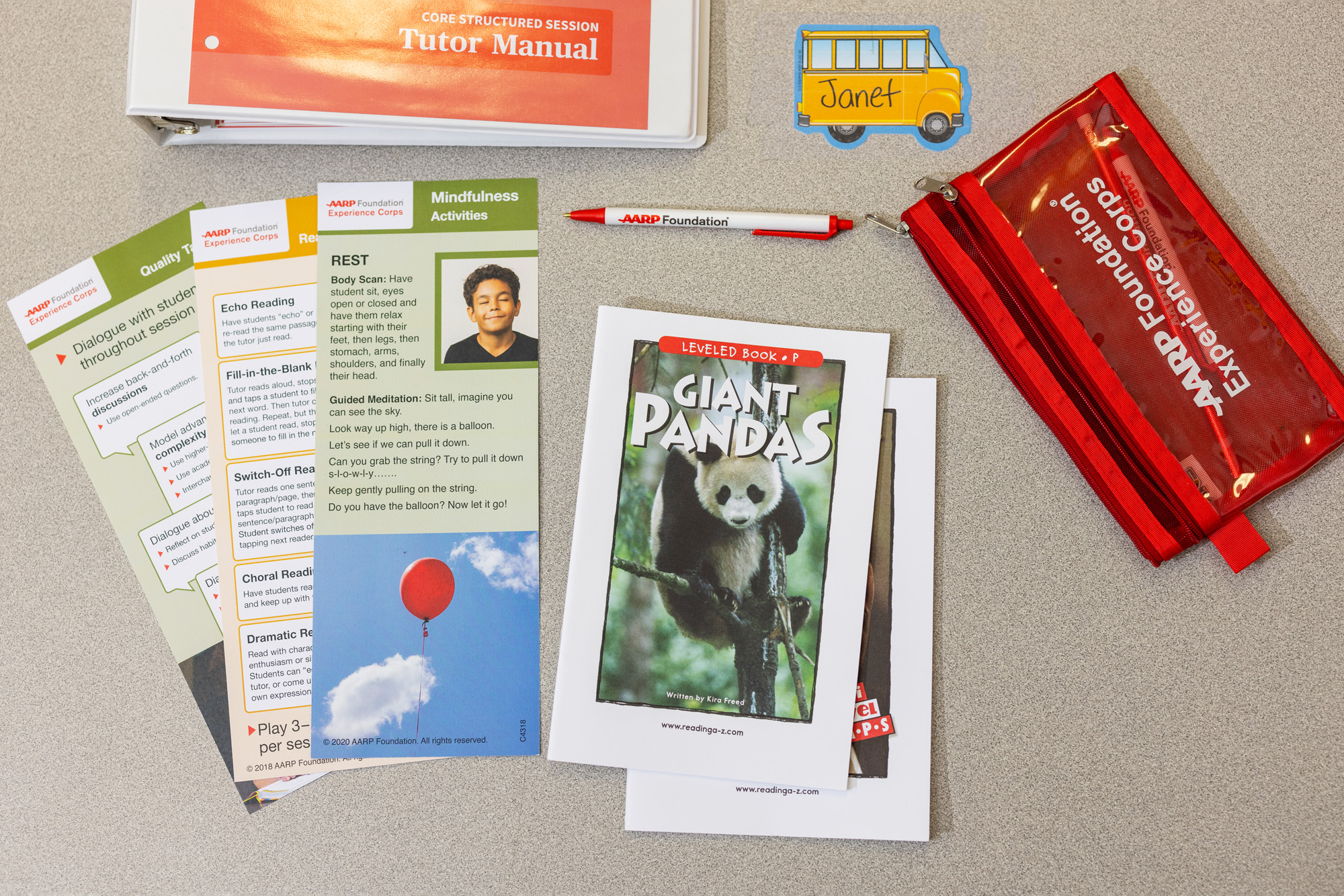

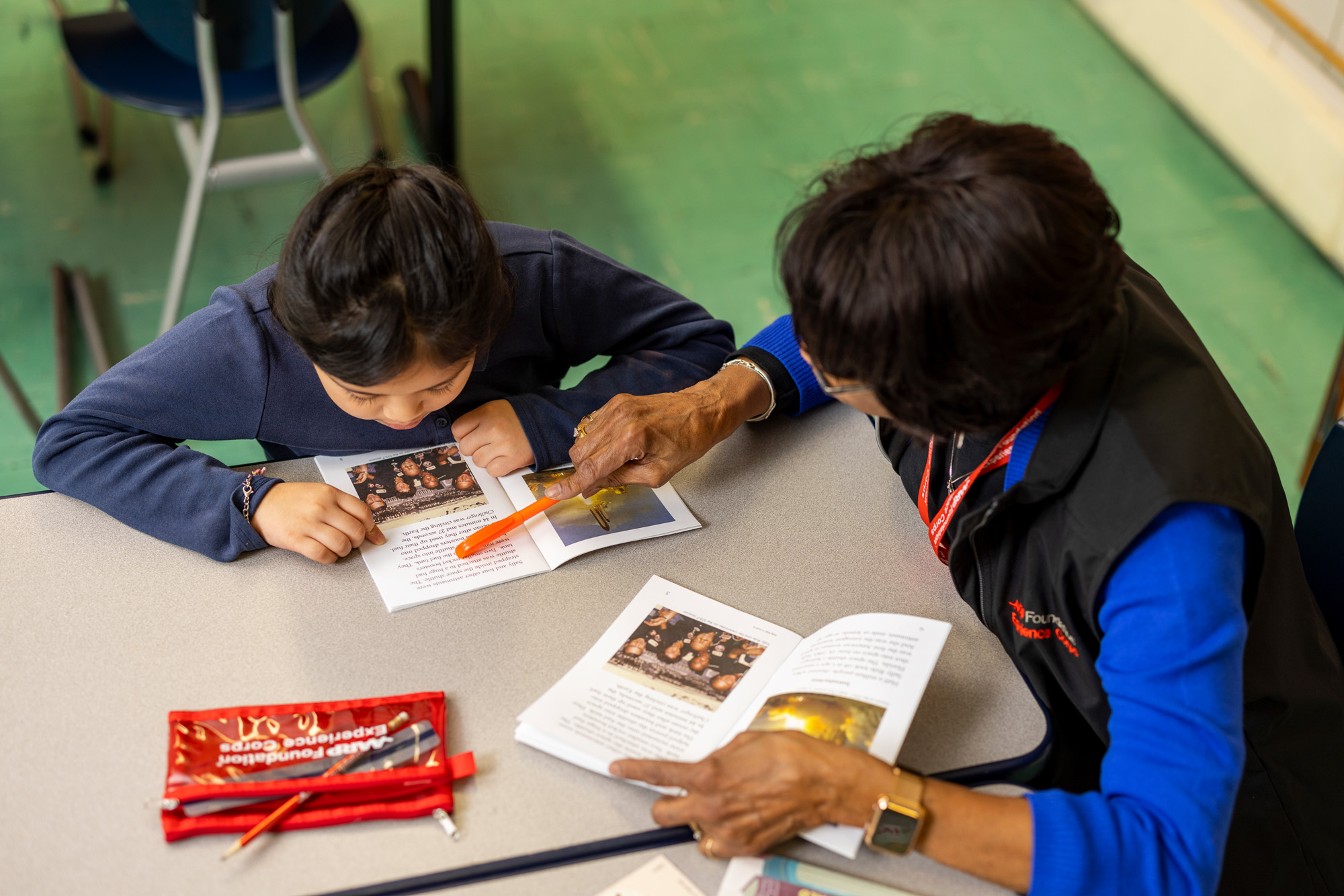

*Responded to Buffalo's high illiteracy rate by sending reading coaches to day care centers throughout Buffalo, helping to prepare children for kindergarten. The Read to Succeed program also includes plans to tutor adults so they can win higher-paying in-demand jobs, such as health care work. Created by the Community Foundation, the program is funded with $500,000 from a trio of foundations. That money attracted another $5 million, including $4.1 million in federal dollars, Dedecker said.

Another, the Josephine Goodyear Foundation, gave $150,000 to adopt East Delavan Library for three years, also with the goal of improving literacy.

*Addressed the city's abandoned houses -- Buffalo has the third highest vacancy rate in the country -- by funding Buffalo ReUse. The two-year-old nonprofit helps restore neighborhoods by taking apart the old houses. It hires and trains young people from the neighborhoods to do the work. ReUse then recycles parts worth saving, selling doors, flooring and bathtubs at its store on Northampton Street. A collection of local foundations has given several hundred thousand dollars, including a $600,000 two-year grant from Oishei.

*Provided additional training to Buffalo school administrators. The Tower Foundation, acting on research that says student performance is linked to the quality of school managers, spent $750,000 in the past five years to create a 10-month leadership training program with the University at Buffalo's Graduate School of Education. So far, about 150 Buffalo Public School staff members have gone through.

*Launched a lead-abatement program, which includes a plan to remove lead paint from 100 homes in the year ahead, to improve the health of people living in low-income areas. Lead poisoning, a threat in any house built before 1978, harms brain development. And, in 2007, 737 children in Erie County had high levels of lead in their blood. Buffalo, said Dedecker, has the highest risk ZIP codes in the state.

"We're robbing these children of their God-given potential," said Dedecker.

The foundation won a $300,000 federal grant for the project and will contribute $134,000.

*Established free tax clinics. After giving $450,000 for the first three years of an enlarged and better publicized program, Oishei staff urged better numbers, said Diane Bessel, a senior product manager for the United Way's Income program, which includes the free tax sites.

Oishei wanted 10,000 returns filed, something Bessel wasn't sure could be done. "We did it and exceeded it because they challenged us to do it," she said.

In 2008, the last of the three years of Oishei funding, 17,881 returns, worth almost $19 million, were filed from 48 sites -- 12 new and 36 newly publicized -- throughout Erie County. Before the grant, the county's previously smaller collection of free tax sites filed 3,847 returns in 2002, Bessel said.

The tally for all three Oishei-funded years: 38,229 returns worth almost $41 million.

The success led to more developments. Last year, an "income taxi" bus drove to rural areas to offer tax refund assistance. To help people make the most of their tax refund money, a free financial planning center will open in January.

"We're hoping to expand the model. Just a friendly place where you can go and get some help," Bessel said.

Peter Frumkin, at the University of Texas, says the foundation strategies to fund innovative programs, such as this, are more effective than what he calls a Victorian-style "spray and pray" model of giving many small grants without a plan for fundamental, lasting change.

"We want philanthropy to play this role as change driver," said Frumkin, author of "Strategic Giving: The Art and Science of Philanthropy."

Finding strategic ways to make the most of foundation money -- especially in these tough economic times -- seems particularly important in Buffalo and Western New York.

On a list of 27 major metropolitan areas, even when Buffalo is expanded to include the region's eight counties -- an area with about a 1.5 million population in 2000 -- it hangs near the bottom: 419 registered foundations with $1.89 billion in assets gave away about $90 million in 2006, according to foundation reports.

That works out to be about $64 in foundation giving per capita. It is far less than Seattle, one of the richest foundation cities in the country. The home to Microsoft computer company and Bill Gates has foundations giving away $610 a person.

It was, in part, the desire to find more willing collaborators to better leverage limited resources that led the Grantmakers Association of 40 foundations to study where Western New York's grant money is going. This year, six among them spent $18,000 to commission the University at Buffalo to find out how many other local foundations there are, their missions and their spending.

The UB survey's initial findings, finished last month, were similiar to The News.' Arts and culture spending ranked higher than the association's director Catherine Gura expected: It came in third place in the UB study, after education and health. Human services, the category most identified with serving the poor was fourth. In the News' survey, arts and culture was even higher: In second place, after education. The News also found human services was in fourth place, after health and medicine.

With its new tally of all the foundations in the area, Grantmaker members hope to find peers interested in teaming up.

"We would like to see more collaboration," said Ann Monroe, president of the Community Health Foundation. "Not lockstep funding so that everybody does the same thing. But so that we know better what each other are doing and where the gaps remain and how we can fill them. And we also then know where likely partners might be." While Grantmakers has no plans to suggest that foundations alter spending to direct more money to poverty-related programs, the group did organize a special workshop to help foundation people understand poverty better.

At a half day session led by Bessel in October, some 22 foundation representatives came along with staff from the nonprofits. People broke up into small groups, got assigned a family persona and an objective of figuring out how to get by on a small budget. Gura was put in a family with a mother laid off, a father working a minimum wage job, a teenage daughter and an elderly mother in poor health.

"I was one of the lucky families because one of us had jobs," said Gura who is executive director of Grantmakers and the Children's Guild Foundation, which gives to programs for children with handicaps.

To make ends meet, her group negotiated with the bank to make partial mortgage payments and bought less food than they needed. "When you're living in that kind of situation, you don't have a lot of time for anything thing else .,.,. You went through that whole situation of how that works and how desperate people get."

She thinks the experience will make her more empathetic and effective when she helps choose what projects to fund.

"You can have a lot of altruistic ideas," Gura said, "but unless you're living it, you really don't know."